Contact Us

Books for Sale About the Authors

Monica Brandies

Free How-to Directions: Make Troughs Three Ways

Events

Book Links

book: Best of Green Space book: Citrus: How to Grow and Use Citrus Fruits, Flowers, and Foliage book: Creating and Planting Alpine Gardens

books: Garden Notebooks

book: Q and A for Deep South Gardeners, 2nd Ed. Books: Rock Gardening Garden Book by Mackey

Customer Testimonials

Horticultural Notecards

Garden T-Shirts Art Gallery

Parade of Troughs Horticultural Notecards

Spring Garden Tips

Fall Notes

Summer Tips

Herbs in Fall

Tips for New Gardens

Tips: Edible Flowers

Winter Reading

Book Reviews

Container Gardening Tips For Bookstores and Libraries

Canadian Orders

Garden Links

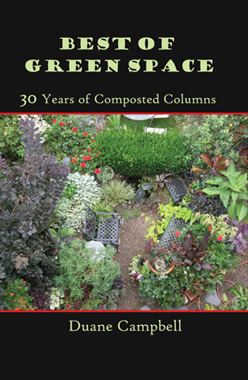

Best of Green Space: 30 Years of Composted Columns Duane Campbell

key Books, Independent Publisher

key Books, Independent Publisher224 pages, 6 x 9 inches, paperback, Best of Green Space is on sale here for $15.00 including shipping. Duane is well known as a syndicated columnist and a teacher of Master Gardeners. He's a great gardener who proves that good advice doesn't have to be boring. If you cross great garden technique with curmudgeonly humor and legendary thrift, what do you get? It is Duane's great cheapological garden advice and many a laugh all through the year. Order this book as a gift to others or yourself. It is ready to ship immediately with personal service from the publisher. Click the paypal button to make the purchase.

Best of Green Space: 30 Years of Composted Columns

by Duane Campbell

Compost

For once the experts got it right. The classic three-bay system is the very best way to make compost.

Youíve seen it on the television gardening shows and read about it in books. You build three open bays side by side by side, each a three foot cube with an open front, like pony stalls.

You pile dead plants in the first bay, and when it is full and the pile has started to shrink, you shovel it all from the first bay into the second. Then you fill the first bay again with new dead stuff. When the time comes again, you shovel all the material from the second bay into the third bay, shovel all the stuff from the first bay into the second bay, and start filling the first bay again. It gives you an intimate understanding of how much a cubic yard really is.

After a few weeks or months, depending on the season and the number of plants that die, you shovel finished compost from the third bay. Brown gold. The closest thing to magic you can do for your garden. Then you refill the third bay from the second, the second from the first, and go find more dead plants.

There is only one little flaw with the classic three bay composting system. No one actually does it. Oh sure, everyone intends to set one up some day, even soon, as soon as he gets some time. But the time never comes and the grass keeps growing and the leaves keep falling. Or maybe the bays get built, but that constant moving from one to two and from two to three and empty three and start all over again gets real old real fast.

Thats why I advocate a simpler system that works because of a secret the experts donít want you to know. Iíll whisper so they donít find out Iím spilling it.

It's true. If you go out into the woods you don't find a three-bay composting system in every clearing, do you? No. Leaves fall on the ground and turn into compost. Eventually.

So I use the all natural, totally organic P&W systemóPile & Wait. I pile the stuff up and wait until itís compost. It takes a little longer, it doesnít get as hot, but it works. After a year or so, I have compost. It may not be the best system, but it is better than a classic three bay array that never gets built.

The one drawback of the P&W system is that you have to wait a year for your first compost. I know people who wonít use P&W because of that, though they have waited five or ten compostless years intending to build a three bay system. Anyway, once your first season is over, your supply of compost is as steady as the guy sweating out his turning and tumbling and moving from bay to bay. As you use last seasonís compost production, next seasonís is piling up.

Just mounding up plant material works. I proved that with Mount Compost, which I shall tell you about shortly when I get to the Things Not To Do part. It works, but cobbling together some kind of frame makes it even easier. And it looks better, if you are concerned with the appearance of your compost pile.

You can buy a compost frame, but the store-bought models have two problems. Theyíre too small and way too expensive. One model, touted as ďOur Most Economical Compost SystemĒ by one catalog, costs forty bucks and holds a measly 22 cubic feet. Whoever cooked up that one sure didnít have a maple tree. One 70 dollar job called a ďkitchen composterĒ is a plastic bucket that you bury in the yard by the back door. We used to call that a hole in the ground, and it used to be a lot cheaper.

And the touted tumbler barrels are hopelessly inadequate for anyone with more than a condo balcony.

For a fraction of the price, a roll of wire fencing twelve feet long by three feet high will give you 38 cubic feet. Or thereabouts. My tenth grade geometry is a little rusty. Make a circle, tie the ends together with twist ties or twine, and start filling it.

Even cheaper, find a pile of wooden skids behind some large store or factory. Ask their permission (which theyíll gladly grant) and take four. Tie them together to form an open-topped cube. In a few years the wood will rot out but the skid mine will still be there.

If you have the urge to actually build something, or if hubby needs a project to get him out of your hair for an hour, hereís a simple and very effective compost frame. Take some lumber that has been lying around waiting for a greater destiny. Pieces 2 x 2 inches work best, but 2 x 4ís will do if you donít want to split them. Make a three-foot square, bracing the corners with plywood triangles. OK, now picture this. You have your square. Using three more pieces, turn it into two three-foot squares at right angles making half a cube. Got that? Good. Now do it again.

You now have two sections, each half a cube. Itís a good idea to dig that half can of avocado green paint thatís been in the basement since 1968 and slap some on to help it last longer. Line each section with chicken wire or turkey fencing, whatever is on sale. Using four screen door hooks and eyes, two each top and bottom, hook them together to make a cube. Now you get to fill it.

Compost snobs who write weighty screeds make it unnecessarily complex. Itís not. But there are a couple of simple things you can do to help the process.

The gurus tell us to mix brown material (leaves) and green material (grass), like the sandwich menu in The Odd Couple. But you may notice this time of year that there is a lot more of the latter than the former. You donít want to pile up all grass, believe me. I save fall leaves in garbage bags to mix with it.

You probably didnít have the good sense to do that, at least not last fall. Youíll have to scrounge brown material. Itís not hard. Look for leaves that stuck in the corners, or get a bale of straw or some sawdust or wood chips. Mix it in with your grass clippings so they donít get all yucky. This coming fall you know what you have to do.

When your frame is full, unhook the ends, pull it off, and set it up right beside your first pile, which will hold its nice square shape. Next spring that first pile will have shrunk to half its height, and though the outside still looks like uncomposted dead plants, inside is brown gold.

I like to sift my compost, but that is optional. I built a cheap frame with quarter inch hardware cloth, and I spend mindless hours running compost through it. I put the finished compost in garbage cans and periodically go out and run my fingers through it like Scrooge McDuck in his vault. But you can take it straight from the pile to the garden if you already have some mindless activity that you prefer.

There are things you should do and things you shouldnít. Do chop up larger pieces into smaller pieces. I put a pair of hedge clippers by my pile and take a few chops whenever I walk by. Donít waste your money on compost starter. Do keep the pile moderately moist but not soggy. Donít put Christmas trees in the pile.

The books donít tell you that. But a while back my first frame, unpainted, rotted out, and I just started piling stuff up until I could get around to building a new one. I threw the Christmas tree on top. Then the next yearís Christmas tree. By the time I got my new frame built, I had Mount Compost. I had to carve steps into the side to get up and dump stuff. When I started dismantling it, the ghosts of Christmas past were a real pain.

So if you opt for the most simple method, piling stuff up, donít put the Christmas tree in there. Or you can make an effective but rudimentary frame cheaply and easily.

If you donít yet have a compost pile, you just ran out of excuses.

*******

Resolutions

It's time for the dismal chore of making New Yearís resolutions. The positive slant is that this is a new beginning. The truth is that we are making a list of all those things that we habitually screw up. I have a ritual. I pull a yellowed paper from my desk, unfold itócareful not to crack the brittle creasesóread the list put together years ago, and resolve once again to do them. Really try this time. Honest.

Some people make new resolutions each year, but I donít need to. I have plenty left over. Donít tell me youíve never recycled a New Yearís resolution.†††††

One leftover is stacked on my desk right nowóa lamp-high pile of various loose leaf, spiral, or fancy garden journals, all with the first few pages meticulously filled in but otherwise empty. If you want to know about my gardening in the first couple of weeks of any January, back to the early 1970s, I can tell you. Donít ask me about June, though.

Another I have actually done, but I need to remind myself every January. Get seed starting mix.

Seed starting mix is a sterile soil mix that is more finely sifted than normal potting soil. In recent years it has sold out early, gone before I actually need it. So as soon as it appears on store shelves, while the last plastic Christmas trees linger at 90 percent off, I get my supply.

I resolve not to order† more seeds than I can use. Yeah, well. Letís move on.

This year I resolve to test suspect seeds at least a month before planting time. I keep seeds, sometimes for years, and their viability dwindles with age, sometimes down to nothing. Itís a good idea to find out before time to start them for real. Too many years I have not had some treasured plant in my garden because old seed didnít germinate.

The process is simple. Count out ten seeds, lay them along the edge of a paper towel, and roll it up tightly. Mark the name of the seed and the date on the towel, wet it well, drain, and put it in a Ziploc bag in a warm spot.

In a couple of weeks, unwrap them and check for a radicle, the beginning of a root, emerging. If none has, but some seeds have swelled, put them back in the baggie for another week or two and check again. The number of seeds that have sprouted times ten gives your germination percentage. If it is zero, there is still time to get new seeds.

This must be done well before you would normally start planting seeds, which brings me to my next resolution. Make a schedule. I used to do this routinely every spring, but I slacked off because I thought I knew what I was doing. I didnít.

Different seeds get planted at different times depending on how long they need to grow to transplant size and when they can go out in the garden. Melons, for instance, only need four weeks to transplant and go out the first week of June, after the ground is well warmed. Onions, on the other hand, need eight weeks and go out in April.

Using a free wall calendar from the bank or the insurance company, I prominently mark the average last frost date, early in the second week of May for me. Thatís a starting point.

Just about every garden magazine at the checkout this time of year has a chart telling you when transplants go out and how long they take. Tomatoes, for example, need eight weeks and go out after the last frost. So take the last frost date, move your game piece ahead one week to be safe, count back eight weeks, and write t-o-m-a-t-o.

For the adventurous, count back another four weeks and write ďtomatoĒ again. This is the early, and risky, first planting. You can warm the soil with plastic mulchóblack or, better still for warming, clearóand protect the plants with water towers or floating row cover. Or you can just put them out and hope the frost date is wrong this year.

Peppers take longer than tomatoes. Lettuce and Chinese cabbage and cole crops are ready in six weeks, but they go out much earlier in spring. Itís all too much for my mind to keep straight, so I will write it all down on the calendar. Now. In January, when I have the time.

Next resolution: Remember to look at the calendar.

********************************************

How about a longer sample? The publisher will email you one in PDF format, free. Ask for the Best of Green Space Sampler from info@mackeybooks.com.

go back to home page